by Viv Wilby

It’s not hard to see Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1964 film, Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to St. Matthew), as a deliberate shift away from, perhaps even rebuke to, the style of religious filmmaking that had poured out of Hollywood in the 1950s and early 1960s. These were gaudy, technicolor affairs, stuffed with earnest matinee idols, hammy character actors and hundreds of extras. Starlets draped in wisps of chiffon would flash kohl-rimmed eyes at pained looking holy men. And just in case we were in danger of forgetting, a stentorian voiceover would remind us that This Is The Word Of The Lord.

In contrast, Pasolini’s film is simple and spare. Shot in stark black and white with a cast of non-professionals, it follows the linear narrative of Matthew’s gospel. We move through the familiar beats of Christ’s life: the visit of the three wise men and flight into Egypt; the baptism in the river Jordan and temptation in the wilderness; the calling of the apostles; the preaching and miracles; culminating in Christ’s arrival in Jerusalem, his betrayal by Judas Iscariot, arrest, trial, crucifixion and resurrection.

There are no gimmicks or special effects here, no tongues of fire or mysterious winds. Supernatural figures are given human avatars. The Angel of the Lord is a wingless young woman in a white shift, Satan a middle-aged man with thick, curling dark hair. Miracles are rendered using the most basic tools available to the director: simple editing. A leper walks towards Christ, cut to Christ who pronounces him clean, then back to the leper who we now see is whole again. An apostle holds five loaves of bread, the camera blinks, and there are baskets holding 50 loaves.

Nor is there much pretence at historical accuracy or consistency. The twelve apostles may wear the plain robes and sandals we have come to associate with first century Galilee, but they are largely a beardless crew, their hair styled into contemporary fashions; Pasolini’s camera often catches the sheen of Brylcreem on their temples. The Romans (such as they are, I don’t recall the word being mentioned) wear battered breastplates and helmets reminiscent of 16th century footsoldiers. The Jewish high priests and Pharisees don bizarre, enormous white headpieces, (part papal tiara, part alien headdress) which set them utterly apart from the common folk.

The overall impression of artlessness is further amplified by the use of non-professional performers. Their reactions are often gauche and self-conscious. Children fidget and scowl, the toothy woman who anoints Christ’s head at the Last Supper grins and shuffles awkwardly, the crippled man who picks his way down a hillside on crutches is clearly not faking it.

Taken together these suggest, not that we are viewing a re-enactment of Christ’s life as it might actually have been, but rather that we are watching a film of a passion play, albeit one with some pretty nice production values. One wonders how the participants viewed their experience. A job? A diverting pastime? An act of devotion?

Overlaying the action, and one of the film’s most striking and modern features, is its grab-bag soundtrack. Pasolini takes spiritual music from around the world, from across history and from classical and folk traditions to underscore the action. It alternates between Bach’s St Matthew Passion, an African choir’s Missa Luba and the spirituals and revivalist music of America. Odetta’s plaintive rendition of ‘Sometimes I feel like a motherless child’ is used twice in the early part of the film. First to accompany the wise men and their retinue as they pay homage to the infant Christ and again as pilgrims line up to be baptised by John in the Jordan. There’s a fascinating juxtaposition here: the loss and longing expressed by the song, the journey towards grace expressed by the action. It’s also a perfect fusion of Christian traditions. Visually, the procession of the devout reflects the Roman Catholic rituals of pilgrimage and adoration, but the music is pure evangelical Protestant revivalism.

Consistent with the anachronisms of dress and music, the film makes no attempt to sketch in the historical and political backstory to Christ’s time on earth or to amplify the role of minor characters. Indeed, everything is so pared back, so focused on Christ, his ministry and the reactions of those he encounters, that supporting characters are often reduced to little more than prompts to keep the story moving forward.

The result can be a disappointing lack of drama. Christ’s trial before Pilate is frustratingly brief and filmed only in long shot. All we see of Pilate is a stocky, dark-haired man in the middle distance. There’s no attempt to explain or contextualise Judas’s betrayal. The character of Mary Magdalene (and any sexual or romantic complications she might bring) is cut altogether. The important woman here is Mary the mother of Jesus. The film begins and ends with a close up on her face. First a beautiful, heavily pregnant young girl staring defiantly at the camera, and finally an aged, sunken-cheeked woman (Pasolini’s own mother, Susanna), overcome with love and wonder.

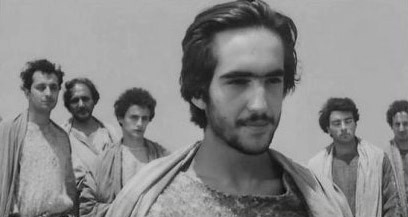

Many commentators have attempted to identify connections between Pasolini’s Marxist politics and his depiction of Christ. This is Christ the civil rights leader, they say, or Christ the revolutionary. There’s an intellectual intensity to Pasolini’s Christ and, portrayed by the 19-year-old Spanish student Enrique Irazoqui, he recalls a young radical. He’s stern, often angry, always in a hurry. He barks out his parables, rebukes the Pharisees for their hypocrisy and delivers the Sermon on the Mount like a fire-and-brimstone preacher. There’s not so much of Christ the lamb here; it’s almost as if he finds healing the sick a rather tiresome duty. The wealthy and powerful are, through the figures of Herod and Herod Antipas, portrayed as idle and cruel. The rich young man, on being told he would have to surrender all his possessions to enter the kingdom of God, turns his back on Christ and walks away.

But set against that is Pasolini’s lack of interest in exploring the political tensions of occupied Judea, something many other less avowedly political directors have done in their versions of the gospel story. It’s, theologically, perfectly orthodox; there’s no attempt to deny Christ’s divinity. And, if we’re being ungenerous, casting your mother as Mary and dedicating your film to the memory of the recently deceased pope, John XXIII, seem like the acts of a sentimental altar boy.

What comes out most strongly from Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo is its celebration of humanity, particularly (but not exclusively) the rituals of the Italian working class. It’s not so much an expression of faith in itself (indeed, Pasolini was an atheist), but a salute to the role religion plays in the lives of ordinary people. Rather than condemning religion as the opium of the masses, Pasolini sees in it the power to transfigure and redeem. His is a populist re-telling of the story of Christ, rooted in the simple, the domestic, the everyday. This is a Christ of the people and for the people.

Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to St. Matthew) is out now on Blu-Ray from Masters of Cinema.