BY JOSEPHINE GRAHL

It’s now almost twenty years since Sebastian Faulks’s novel Birdsong was first published and it comes as something of a surprise to realise that it has never yet been brought to the screen. It seems like a tale that’s ripe for adaptation, with its potent combination of passionate sex, the horror of the trenches, and book sales in the millions. Several versions have been proposed but none had come to fruition until so-hot-right-now writer Abi Morgan (who has two films, The Iron Lady and Shame, out this month in addition to Birdsong) and director Philip Martin adapted the book into two ninety-minute television episodes, beginning this Sunday, filling what is already described as the ‘Sherlock’ spot.

Stephen (played by Eddie Redmayne) is a young man visiting factory owner René Azaire to advise him on his textile mills in Amiens, northern France. He falls in love with Azaire’s wife Isabelle (a luminous Clémence Poésy) and they have an affair. Six years later, Stephen is a lieutenant in the trenches of the Western front in charge of a company of tunnelers responsible for mining underneath German trenches. The film flips back and forth between 1910 and 1916, contrasting the beauty and serenity of bourgeois Amiens with life in the trenches.

Martin and Morgan have spoken about their intention to get away from highly politicised interpretations of the First World War such as Richard Attenborough’s film of Joan Littlewood’s revue Oh! What a Lovely War. Setting aside the question of whether it’s even possible to ‘depoliticise’ a historical disaster in which over 35 million people died, there’s certainly space for a more nuanced take on the conflict than Oh! What a Lovely War – which is, let us not forget, a Brechtian musical satire rather than a realistic depiction of war – but Morgan and Martin’s Birdsong is not it. In depoliticising the war, in trying to avoid the clichés of beautiful and doomed youth, lions led by donkeys, Birdsong adopts other clichés: the one about the Edenic pre-1914 world, lost forever in the horror of the trenches; another of the highly strung officer, muscle twitching in his jaw, unable to bear the horrors that rougher men take for granted. Even the relationship between Isabelle and René is crashingly unsubtle: he is the strike-breaking capitalist whose impotence makes him beat his wife; she’s the angelic innocent who secretly takes bread to his striking workers.

In the trenches, upper-middle class officers rub shoulders with their working class troops: but the painful contrast between sensitive, tortured Stephen and his jovial, buffoonish men is roughly as patronising a take on class as Downton Abbey with its beautiful, kind-hearted aristocrats and comically rustic servants. Traumatised by his unhappy affair and by life in the trenches, Stephen plays sadistic games of chance with his company: but somehow, of course, they see the quality in him and respect him anyway. It’s a shame that the character of Jack Firebrace, the tunneler serving under Stephen, has been stripped down for this adaptation; where in the novel Firebrace is described as constantly sketching and has a backstory of his own, in this version it’s Stephen who is the artist. Although Joseph Mawle does wonderfully with what he’s given, Firebrace’s main function as a character is to offer an earthy working class contrast to his overwrought officer.

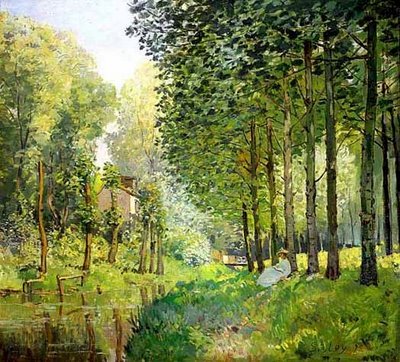

Visually the direction is lovely. The gorgeousness of the sections set in pre-war provincial France recalls the paintings of Alfred Sisley or Camille Pissarro. The contrast with the trenches could not be more pronounced: the juxtaposition of the apocalyptic bleakness of no-man’s-land with the golden serenity of afternoon tea under the trees is very effective. The flashback form is a clever reminder that these two eras, separated by just six years, share the same geography: Amiens was right in the middle of the Western front and where the final Allied offensive began in 1918. The shattered trees standing in the mud of the trench sequences, it’s implied, may well be the same trees as the elegant limes under which the Azaire family picnicked in 1910.

That juxtaposition is reflected in the action. Asked what made Birdsong an adaptation for the 21st century, Abi Morgan suggested that an earlier adaptation might not have been able to render the sexual content with quite such intensity. There’s a deliberate parallel between the way the love scenes and the battle scenes are filmed – speaking at the preview screening, Philip Martin said he had wanted to emphasise the similarity between the drama of war and the drama of love: “they are the most extreme things you can experience in life; in love and in war, everything is ten out of ten.”

What Birdsong does very well is to capture the physical reality of life in the trenches. The passages set in the tunnels have a queasy claustrophobia that reminds one of helmet-cam footage from Iraq or Afghanistan. The bodiliness of the war, where soldiers in such close proximity to each other lose their inhibitions, and death and mutilation become everyday events, is nicely done: Stephen observing the musculature on a corpse; the rows of naked men laid out by the hospital tents, their grubby, waxy skin contrasting with the luscious sunlit flesh of the earlier love scenes.

In these moments the film succeeds as Morgan and Martin intended: the First World War not as history or politics but as lived experience. But the sights and sounds of the trenches are only part of the lived experience: the pathetic and bathetic class stereotypes undermine the honourable attempts at realism.

Part 1 of Birdsong will be broadcast on BBC1 at 9.00pm on Sunday 22nd January. MostlyFilm thanks BAFTA for hosting the preview screening of Birdsong

Josephine Grahl blogs at Nothing was disastrous

The Sisley picture is Le repos au bord du ruisseau (Rest by the edge of the stream).

I’m watching it at the moment. It looks lovely, but I’m just not feeling it.

I saw part one and felt the two leads were an attractive duo, but there’s no sense of drama. Which, considering he’s facing death in the trenches and flashing back to falling in love with the wife of the man he is staying with and then having an affair with her under said chap’s nose, is a pretty disasterous void. The lead chap has an interesting face, as does the leading lady but lingering shots of lingering looks is not enough to portray turmoil.