by Ann Jones

It’s often easy to get lost in one’s own thoughts looking at a piece of art; paintings and photographs can suggest stories or remind us of familiar narratives but it’s up to us to fill in the gaps and, while we might be lost in the moment, we’re inevitably on the outside looking in. In the cinema the story is easier to follow; more often than not the narrative is linear and there is dialogue drawing our attention to the things we shouldn’t miss. Films are populated by a cast of characters with whom we form some kind of connection, however short-lived. But no matter how much we suspend disbelief and get caught up in the story, we’re safely on the outside looking in. In Mike Nelson’s work all that changes.

Visiting a Mike Nelson installation is always, for me at least, an intriguing experience. I like trying to fill in the gaps, working out whose world I have wandered into, where they have gone and when they will be back. There is something of the same fascination as looking round someone else’s house, but without the comfort that comes from some level of familiarity. These are not places I can imagine ever being part of my own day to day life, and the story I piece together is one of people on the margins, either deliberately or through circumstances I’m fortunate enough not to comprehend.

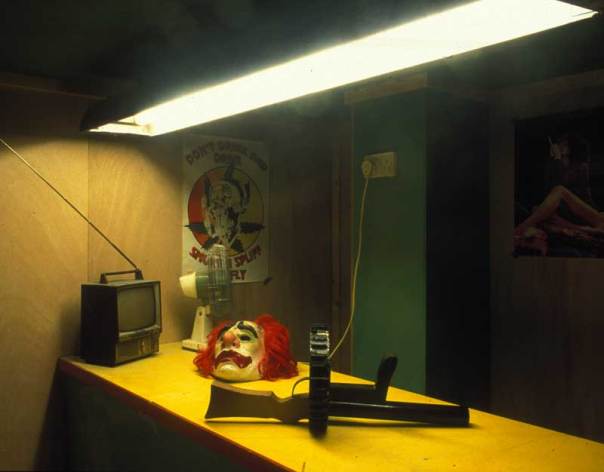

Coral Reef, first shown in Matt’s Gallery in east London in 2000 and currently on show at Tate Britain, lets us wander through a labyrinth of familiar and unfamiliar spaces accessed through grimy creaking doors, entering through a run down gallery reception area. It’s easy to get lost, not in one’s own thoughts as one might in front of a painting, but in a space that plays tricks on the visitor. While we’re still definitely on the outside looking in in one sense, physically we’re right there, trespassing in a world we don’t quite understand, always aware of our own presence in a series of deserted corridors and rooms. These are spaces that doubtless exist somewhere, but who populates them? And will they come back soon? The creaking doors tell us we’re not alone, but still it’s hard not to jump and look slightly shifty when we meet another visitor. Many of these spaces are made for waiting but few would choose to sit on the grubby sofas or rickety chairs. Instead we navigate the space carefully, pausing briefly to furtively look at the books and calendars – ever mindful of our own suspicions that the rightful occupants of these rooms could return at any minute – and always on the move, anticipating the next dilapidated room.

Increasing the sense of uncertainty about whether or not one has wandered away from the public areas of the gallery, for those who have done their research before visiting, on separate pages the Tate website confusingly confirms Coral Reef as a past display and a current one.

The people who occupy these rooms – who work in the minicab offices, use the drug paraphernalia, or sleep in the sleeping bag on a dirty floor – are part of the city but a part we seldom see up close. Our journey through their space, particularly within the hallowed halls of Tate Britain, is a reminder of the less comfortable lives of people on the margins. In Matt’s Gallery, an east London warehouse space, more than a year and a half before 9/11, Coral Reef was a very different experience seeming more connected with the end of millennium (the work was made in 1999 and opened in January 2000); perhaps inevitably now our response to the evidence that some of these spaces are the domain of people who we perceive to be Muslims – on the evidence of the calendar, books and posters – is affected by the events of the intervening decade. But there are many belief systems to be found here from Mexican communists to evangelical Christians via drug users and bikers. These are liminal spaces: reception areas and corridors; in many we find ourselves on the wrong side of the counter having apparently strayed from the public area to someone’s work place. Many rooms have more than one door; we are always in a state of transition and there is no single path through the work. The occupants of the spaces seem to be almost equally transient; these are not spaces in which roots are being put down, there is a sense that returning to the same place a week later might feel very different. The first room we encounter on leaving the gallery reception – the Islamic mini-cab office – is repeated, adding to our confusion. We have wandered into someone else’s world and though we are free to pass through it at our own pace, we all too easily find ourselves trapped within it, caught by our own curiosity and nosiness.

Having visited Coral Reef several times recently, I know that in reality I won’t get lost. I won’t get trapped overnight and need to use the grubby sleeping bag or curl up on a cheap sofa that has seen better days. I also know that I will meet other people in there – if no-one else, then there’ll be a Tate guard in there somewhere – but I’m always surprised when it happens even though the creaking of the doors acts as a warning signal. Usually I meet the same person several times. I always want to make sure I don’t miss anything; often the people I meet are looking for the speediest possible escape. There are several different stories here: there are the narratives implied by the rooms, as complex or as simple as we want to make them: stories of life on the margins, of the hidden layers of urban life, of the numerous belief systems underpinning society, of transitional spaces and of impatiently waiting in a world where we are too busy to just sit. There are also the narratives of my journey though the work and those of the people I meet and of course there is the narrative of the guard, constantly surprising people, catching us unawares even when we know he is there.

In stark contrast to the grubby waiting areas of the Coral Reef, elsewhere in Tate Britain I do spend time just sitting watching: somehow Mark Wallinger’s Threshold to the Kingdom (2000) demands it. Here I sit on a hard museum bench, a little too deep to allow me to lean back against the wall but still offering welcome comfort after Coral Reef. As I watch a story of waiting, arriving and crossing a threshold is played out in slow motion on the screen in front of me. This is a comfortable, populated space. People sit and wait, automatic doors open and people arrive either to pass straight through the space or to be greeted. Some look happy, some businesslike, some wave at those waiting to meet them, most pull suitcases or push trollies with the wearied air of the traveller nearing the end of their journey. The narrative element here is akin to trying to work out the relationships between people in a cafe or trying to work out where the person sitting opposite on the tube is going and why. But Wallinger gives us more than an idle exercise in people watching. The combination of the title of the piece and the choral music that fills the gallery suggests that the threshold is to another world. More prosaically it is in fact the international arrivals area of London City Airport; these are visitors to the very same city that Nelson’s Coral Reef inhabits, though few would ever imagine, much less experience, the spaces he offers us.

Threshold to the Kingdom is intriguingly situated. The room is octagonal, the screen is straight ahead as I come in, so that I have been drawn to it from a couple of rooms away; I sit and watch for several cycles of the work, mesmerised by the music and the way the slowness makes the ordinary somehow much more compelling; there are moments when collisions seem inevitable as those waiting cross the path of the new arrivals. By definition, airport arrivals is transitional space where people enter or reenter a country. At Tate the work has been installed such that it too sits at a border between two connected worlds. I enter the work through galleries full of recent and contemporary art; I exit through the gift shop.

Mike Nelson’s “Coral Reef” either is or isn’t on display at Tate Britain depending on which part of Tate’s website you believe. My own experience is that it is. Try Room 28. Mike Nelson is representing Britain at this year’s Venice Biennale.

Mark Wallinger’s “Threshold to the Kingdom” is also on display at Tate Britain

Another inspiring piece Ann – you always make me want to go and see the works you write about. I wonder that Coral Reef might not be at its best at weekends though, which is the only time I could realistically see it atm. Shame.

It definitely benefits from being seen without sharing it with a group of teenagers prone to screaming at regular intervals, as I did recently. From what I can gather it’s likely to be there until the end of the year but getting a definitive answer seems tricky.

I saw Coral Reef first thing on a Saturday morning, and it was quite deserted – just get there before the crowds. Ann’s right, it’s quite magical when there is no one else there (I didn’t even encounter the guard until I was almost done.)

Oh, I love Mike Nelson. Triple Canyon Bluff at Oxford was one of the eeriest and best things I’ve ever come across

Absolutely brilliant review…spot on analysis of both works and the first pieces here that I find my young kids reallly genuinely curious about..and a similar reaction with Nelson’s space at the Biennale with a school group earler in the year.

The Tate website now shows Coral Reef as closing on 15 January 2012 (this Sunday). I will miss it. (Although as the Tate website still shows it as both a current and past display, who knows whether it’ll actually close.)

Reblogged this on H.G. Fields and commented:

This may well be the best piece of art I’ve ever experienced in any medium. Ever. I’d love to see this installation again after having done so, in November 2011. I was well disappointed earlier this year when I returned to the Tate Britain to experience it all over again, only to find that exhibit no longer exists.

Quite interesting how such a vast and intricate installation could be there for so long and then just like that, wuff. Mind you it probably wasn’t all just like, “wuff” to all those who were personally involved.

In any event, I wish anyone who reads this that they would one day have the opportunity to live the other worldly experience that is, the “Coral Reef.”