Paul Duane on how Simon Nye’s How Do You Want Me? Refashioned a vile classic into a poison-pen paean to Englishness.

To start with, let’s take two things as given: first, that the 2011 remake of Straw Dogs by Rod Lurie is an irrelevance and an embarrassment, and useful only as a peg on which to hang this poorly-thought-out but long in gestation article; and second, the original Straw Dogs is in itself a problematic, troublesome turd in the punchbowl of Sam Peckinpah’s crazed career. (If you disagree with either of these givens, that’s the comments section right over there ——->).

Now then. Back in the late ’90s, the sitcom genre was quite a different beast. The League of Gentlemen were a successful but oddball bunch of sketch comedians just trying out their talents on television, buried on BBC2. The Boosh and the Conchords were not yet born. Situation comedies tended to be a gentle battle of the sexes, or a lightly humourous clash between different varieties of working-class people and homosexuals. And the king of all he surveyed was Simon Nye. His series Men Behaving Badly was a battle between two men, one jug-eared, one not, to remain childish, irresponsible monsters well into adulthood. It was hugely successful.

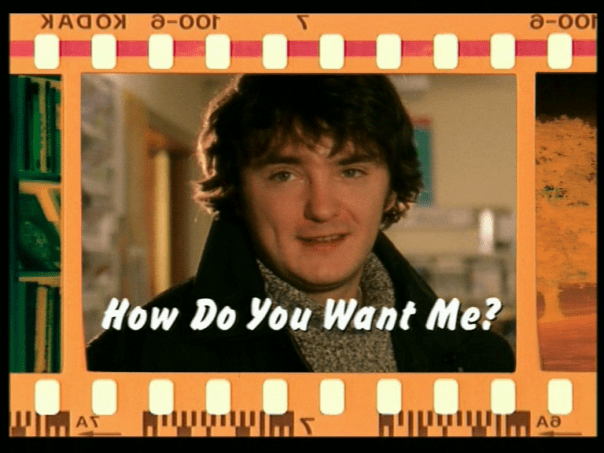

His next outing – How Do You Want Me? – wasn’t. Not surprising, in a way, as it’s one of the strangest, most unclassifiable products of that era, and one that still feels challenging and uncomfortable even now that we have sitcoms featuring leprous undersea transexuals based on Rick James (The Mighty Boosh) and ones where elderly bald men instruct teenage girl guides on how to insert tampons (figure it out yourself).

Here’s where we get back to Peckinpah. HDYWM’s storyline is basically a collision between Straw Dogs and the scenes in Annie Hall where Woody Allen visits Annie’s family in the midwest. Except played, mostly, for laughs, even if they’re of the blackest and most unsettling variety.

Comedy promoter Ian Lyons has married his girlfriend Lisa and moved with her to Snowle, the quaint little Home Counties village where she grew up. Once settled in there, he has to deal with her extended family: in particular her father – ferocious battery-turkey mogul and patriarch Astley (Frank Finlay) – and her brother, psychopathic builder/fireman/hooligan Dean (Peter Serafinowicz). He hates them, they hate him. That’s it, that’s the whole thing.

In this interview, Nye explains that he’d set out to make a “more attractive portrait of rural life” but that somehow, he was “genuinely slightly surprised by what came out”. I can well believe it.

The show Nye presumably set out to make is the one promised by the opening credits – twee, sepia smiling portraits of the stars, accompanied by a cozy, boozy blues harmonica. However, the show he ended up making is full of suppressed violence, rage and unhappiness, bursting at the seams with strange bits of comic invention and some genuinely unsettling bits of story. For instance, when Dean, for a laugh, posts stolen nude photos of his sister all over the village, or admits to wanting to have sex (but not a relationship) with his other sister… or when Astley offers his son-in-law fifty grand to just disappear, or when Ian, pushed over the edge towards the end of series 2, shoots Astley in the back with a shotgun.

It’s not hard to imagine any of these scenes playing out in a ‘serious’ drama, and the fact that they’re wrapped up in the cotton wool of sitcom visuals (they must have spent a fortune on ‘hazy golden sunset’ filters for the landscape) makes them all the more disturbing and memorable.

So how did this Home Counties apocalypse come about in the first place? A large part of it has to come from its then largely unknown star, Dylan Moran. He wanders around in a fug of inchoate resentment, mutters things like “Living here is like being in Peking during the Cultural Revolution’, and generally behaves like a real life version of Bernard Black. His presence, it seems to me, turns the whole show on its head. Instead of being a story about a city slicker who can’t get on with the country bumpkins, it becomes a story about two completely different modes of communication.

I don’t know at what point it was decided that Ian had to be Irish, and thankfully there’s hardly any reference to it in the script (is that what they call ‘colourblind casting’?) but it skews the entire story in a fascinating direction. This is a very middle-class horror story, and having an expatriate Irishman at the centre of it brings out the innate weirdness of the Home Counties to an excruciating degree. Don’t get me wrong, Ian’s weird too – it’s just that he’s weird in an interesting way.

Moran walks around, talking off the top of his head in that free-associative way that he does (apparently around 75% of his dialogue is improvised – Moran had no idea that you don’t mess with the words of a comedy demigod like Nye, nobody stopped him, the results were so good that most of the improv made it into the final cut) while everybody else talks about what’s in front of them. They’re filled with good old English common sense, he’s away with the fairies, and everyone apart from his his wife either ignores him or wants to kill him.

This is not an exaggeration. There are a few confrontational moments between Dean and Ian that are genuinely scary – particularly because Serafinowicz brilliantly characterises Dean as a likable, easygoing sort, prone to saying things like “See, what I don’t get about Freud is…. who he is.” But then, if he perceives some insult to his family, or himself, or his friends, or the can of Grolsch he’s drinking, his eyes start to go glassy and you realise you’re about to see somebody, probably Ian, getting hit very hard. It’s possibly the best performance Serafinowicz has ever given, and I’m not saying that lightly. The father and son psychopath team that he and Frank Finlay make up may also be one of the scarier portraits of the English family outside of Nil by Mouth. And England and Englishness don’t come well out of this series, all in all.

The English countryside has rarely looked so uninviting on television as it does here. Ian takes refuge in the local pub, but nobody except Dean will talk to him, and then it’s only to ask his opinion on the difference between sodomy and buggery (which he then broadcasts loudly, as in “Ian says buggery can be animals, but sodomy’s just anal sex.”) The rest of the villagers tend to be halfwits or colossal mediocrities, but when Ian’s ‘celebrity’ friends (Marc Warren, perfectly cast as a dim observational comedian best seen half-cut) come to visit, they’re equally awful. Ian takes refuge in wine and rudeness, and is constantly balanced between running back to London and staying just to piss off his relatives. Also, of course, he loves his wife.

Lisa is played by the late Charlotte Coleman in what was to be her last role of any substance. There’s zero chemistry between her and Moran, which should be a probem but actually isn’t, particularly. Her early and tragic death has given the show some retroactive pathos, and her performance is sufficiently charismatic that you don’t find yourself wondering why she and Ian are together, or why she wanted to come home – she loves her awful family, she loves the countryside, she’s a schoolteacher. It’s the right place for her, the wrong place for Ian, and the combination is believably appalling in its implications.

Unlike Straw Dogs, there’s no orgiastic release for Ian Lyons. He doesn’t learn to be a man. His ‘journey’ is really just the development of a dogged commitment to staying in Snowle despite bribery, threats, attempted murder, and horrendous boredom. He starts to figure out that, even if he’s horribly unhappy there, he’s with the person he loves. The fact that that is itself a trap is the really difficult pill to swallow.

Like Straw Dogs, the eruption of violence that has lurked under the story’s surface has to come out somewhere, sometime, and here it’s in the context of some nice, harmless skeet shooting, when Ian discovers that his father-in-law is happy to cheat in order to continually feel superior to him. He turns and, almost without volition, discharges his shotgun into Astley’s back. It’s a shocking moment, not really like anything else I’ve seen in a sitcom. If Larry David came home, mistook Leon for a burglar and stabbed him, that might come close, but it’s unlikely to happen. This, as much as the other, more publicised transgressions that began to sneak in around the end of the twentieth century, is where comedy started to grow up. And like Dustin Hoffman, Dylan Moran ends his story here with a note of great ambiguity. The last line, spoken by him as he sits in a car with his wife, on the verge of leaving town, his only alternative being prison (Astley has pledged to prosecute him if he stays, and he owns the local judiciary), is “I don’t know what to do now.”

The third series never happened, Charlotte Coleman’s untimely death made sure of that. Moran’s TV persona devolved into the knockabout Withnailisms of Bernard Black, and Nye continued to explore human awfulness in the underrated, underseen Beast (about a vet who hates animals, but took the job because he thought it’d impress women). The vast and terrifying spaces of the English countryside, filled with murderous builders, Tory megalomaniacs and strangely mesmerising duckponds, have been lightly explored in such intriguing and diverse Britflicks as Skeletons and My Summer of Love. None of them has hit a nerve like HDYWM. I’m still waiting for Simon Nye to take on Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, but it doesn’t seem likely to happen any time soon.

God, I *loved* this show, but haven’t thought about it for ages.

Reading this has made me order the DVD – you can get both series for less than a fiver from Play.

Absolutely brilliant piece about perhaps my favourite show of all time. It also skewers the reality of the huge wave of “let’s move the the countryside” fantasy that the urban middle class has been sucked into in the years since; half of my current circle of friends are couples where one partner has dragged the other from civilization back to their childhood home.

I loved this show too. Though as Mr S was born into an exact facsimile of the village in HDYWM, we can safely say that the nearest we’ll get to moving to the countryside is a house on Blackheath Common

Possibly the best write up of any under the radar TV comedy gold that I have read. And if you read this and don’t jump straight on to Amazon or Play to order a copy – what is wrong with you?!