by Ann Jones

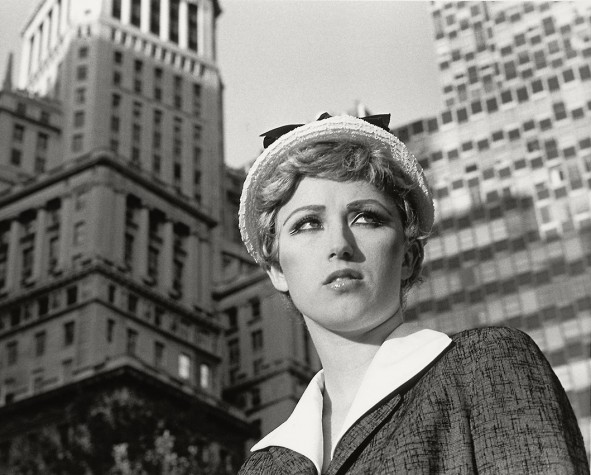

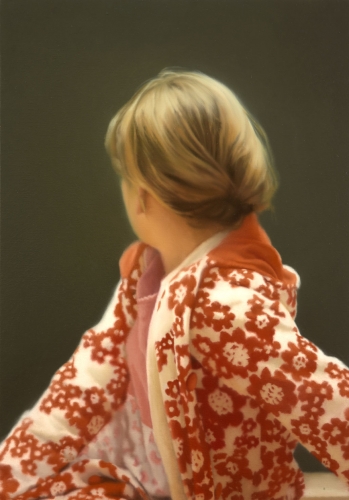

I can never quite decide about Cindy Sherman. I’ve seen countless photographs of her but none that really counts as a portrait; all I really know about her is that she’s a very good actress. I know roughly what she looks like of course, but as she’s something of a chameleon even that knowledge is woefully approximate. Sherman has made plenty of work that I really love but in amongst the great stuff there’s also plenty that leaves me cold, and even the work I like has a habit of downgrading itself in my head when it’s out of sight so that I always suspect I’m misremembering it. All this is probably why a couple of months after seeing her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, I’m still working out quite what I want to say about it and simultaneously thinking I really should have written about it sooner. Hmmm.

Continue reading One face, a thousand lives: Cindy Sherman at MoMA